With the widespread use of the telegraph throughout the North American

continent for over a century, it is easy to assume that success was

reached from the very beginning of its employment. Such was not the case.

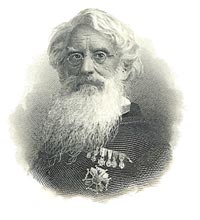

Samuel F.B. Morse labored for several years to perfect and promote his

invention. As early as 1832 Morse had an interest in developing a

practical Morse had an interest in developing a practical electro-magnetic

telegraph. At that time little was known on the subject. Several men

before him had engaged for decades through trial and error with the

principles of electricity. By the end of 1836, Morse had completed his

first telegraph apparatus, crude in form but capable of both sending and

receiving messages using a numerical code which represented letters of the

alphabet. With the help of a colleague, Professor Leonard Gale, several

improvements were made upon the apparatus. In the autumn of 1837 an

exhibition of the working apparatus was given by Morse to friends and

professors at the University of New York. At that time, Alfred Vail took

an interest in one of the inventions, and a partnership was formed between

the three men. Morse was fortunate to have joined forces with both Vale

and Gale, since each gentleman had knowledge which aided Morse in those

formative years of the telegraph.

Samuel F. B. Morse (The Telegraph in America, Vignette)

In February 1838 Morse traveled to Washington D.C. to demonstrate the invention to the president of the United States and to other important politicians. A recommendation was made for an appropriation of $30,000 to aid in the construction of an experimental line. While the money was not appropriated by the government at that time, Morse did succeed in stirring the interest of some high-ranking politicians. Still, the importance of the invention and the impact it would have as a communication system for the world went largely unrecognized. It was not until March 1843 that another telegraph bill, put before the Congress, was passed to appropriate $30,000 for the building of the experimental line between Washington, D.C. and Baltimore, Maryland. Finally, after years of struggle, Morse received financial aid from the U.S. government to promote this invention.

An agreement was drawn up with the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad for the use of its right-of-way for the building of the line. It was decided to lay an underground line using a cable consisting of wires enclosed in lead. Ezra Cornell was entrusted with this work. He had devised a trenching machine for laying cable. The autumn of 1843 saw the work underway. By December, the cable had been laid from the railroad station in Baltimore to Relay, Maryland, which was several miles away. With more than half the appropriation having been spent by that time, great concern was felt by the builders when the insulation on the wires in the cable was found to be faulty. The work was suspended, and a new plan to erect the wires on poles was chosen.

With the arrival of spring 1844, construction commenced once again. One of the main challenges facing the line builders was developing a means of insulating the wires at each pole. Cornell had devised a plan which consisted of sandwiching the wires, wrapped well in cloth saturated with gum shellac, between two plates of glass. This arrangement was inserted into a notched crossarm, over which a wooden cover was nailed to serve both as protection from rain as well as to hold the insulated wire in place. Two copper wires were strung in this manner between Baltimore and Washington. The line was completed, and on May 24, 1844, the first official message was sent. The words made famous on that day nearly a century and one half ago: "What hath God wrought."

Following the completion and successful operation of the line, Morse attempted to convince the mend of government of the great advantage it would be for all of mankind to have the U.S. government purchase control of the telegraph rather than have it go into the hands of private individuals. Even though the experiment had proven successful and the public had shown an interest in the invention, government leaders did not have confidence in the financial success of the telegraph. It seemed unlikely that the number of patrons would be great enough to pay for the expenses involved in operation and maintenance of the lines. Therefore, Morse and his partners turned to private funding for the building of the lines which were to follow.

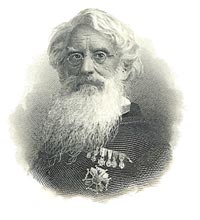

Amos Kendall (The Telegraph in America, p. 113)

In 1845 Amos Kendall, who had previously been appointed by Morse as his agent, took steps to organize a company which would build a line from New York to Baltimore and on to Washington. Due to the lack of funds available at the time, for such a large undertaking, it was decided to first solicit only enough funds to build the line between New York and Philadelphia. The incorporation of the first private telegraph company in this country was grated by the legislature of Maryland, and the Magnetic Telegraph Company was formed. James D. Reid, in his book, The Telegraph in America, 1879, describes the events that followed:

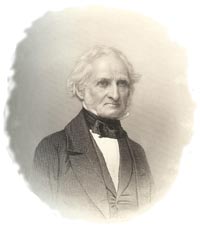

The construction of the line was given to Dr. A.C. Goell, an excellent, energetic man, who built, at a subsequent period, most of the lines through southeastern Pennsylvania. Mr. Cornell personally directed the construction from Somerville to Fort Lee. The poles were small and two hundred feet apart. An arm thirty inches long, with a pine at each end, bearing a glass bureau knob, an insulation proposed by Mr. Cornell and approved by Prof. Henry, was secured to the upper end of each pole.

Bureau knob line construction. (The Telegraph in America, p. 116)

Around the bureau knobs the conducting wires were wrapped. The wires were copper, No. 14, and annealed. The route of the line was from the Merchants' Exchange, Philadelphia, via the Columbia Road to Morgan's Corners, thence to Norristown, Doylestown, and Somerville, to Fort Lee, by the ordinary wagon road. (The Telegraph in America, p. 116)

Early in November 1845, the line was first opened between Philadelphia and Norristown, Pa., distant fourteen miles, so as to gratify public curiosity, while the building was going on beyond. The office in Philadelphia was on the second floor of the Merchants' Exchange. (The Telegraph in America, p. 117)

The line stopped at Fort Lee, since a method of spanning the wide North River to New York City had not yet been devised. A submarine cable had been attempted and proved a failure. Eventually two wires were strung from Newark to Jersey City, New Jersey, and from there messages were sent across the river on ferryboats to New York. The line to Fort Lee was no sooner completed when the insulators became a target for stone-throwing boys and marksmen. It was only the beginning of a problem that still exists today for owners of open wire circuits. A major setback occurred when freezing rain accumulated on the open wires one night and high winds the next day took down many miles of wire. The line was rebuilt with an iron cord of three strands.

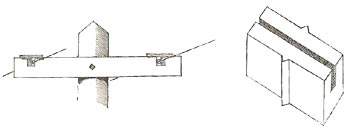

The line from Philadelphia to Baltimore was built by Henry O'Reilly in 1846 with a single iron wire. It was insulated merely with India rubber cloth wrapped around the wire and held in place with pine plugs. Difficulty arose using his method, and soon small glass blocks with V-shaped projections at the center were substituted.

Glass block with v-shaped projections. (The Telegraph in America, p. 123)

It did not take long for other lines to be constructed throughout the East which headed in all directions. By 1850, thousands of miles of wire had been strung, with lines reaching south to New Orleans, north to Maine and westward to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and Dubuque, Iowa. Our northern neighbors had constructed a growing network of lines throughout Canada, primarily belonging to the Montreal Telegraph Company which was organized in 1847.

With this rapidly growing industry came a great need for insulators. It was unfortunate that little was known about insulator by the telegraph companies of the time. Some companies were struggling financially from the start and if they happened to make use of poor insulators, it spelled death to many of the organizations.